Old Trees and the People Who Know Them

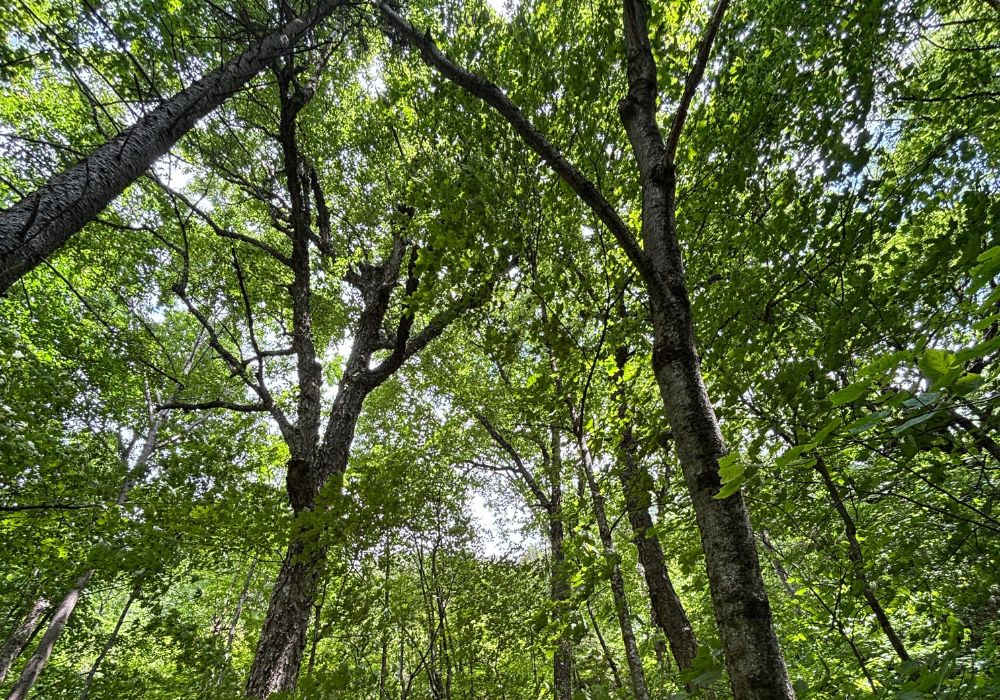

On a cool and breezy summer afternoon, a team of seasoned ecologists and I made our way across a steep talus slope in a remote section of Vermont’s Groton State Forest: a 25-acre stand of ancient hardwoods known as Lords Hill. Tucked into the hills of the town of Marshfield, this forest is a rare remnant of an older age—one of the few places in the state where towering sugar maple, yellow birch, white ash, hemlock, and basswood have been left to grow, die, decay, and regenerate largely undisturbed for centuries.

We were there to revisit a long-term monitoring plot established decades ago and to measure the diameter of trees tagged as early as 1977. With me were ecologist and naturalist Charlie Cogbill, our leader, NEWT board member Brett Engstrom, NEWT’s Wildlands Ecology Director Shelby Perry, and Rose Paul, former director of Science and Freshwater Programs for The Nature Conservancy. We slowly and systematically worked our way across 50-by-20 meter grids, calling out data while Charlie stood at each grid’s center, clipboard in hand, scribbling notes, and confirming each measurement with familiarity and enthusiasm.

“Yellow birch. Tag number 451. Diameter 72 centimeters!” I called out across the talus slope, my voice bouncing off of moss-covered granite boulders.

Charlie, perched atop one such boulder, flips through his notes. “Yellow birch… 451… YES!” he exclaimed triumphantly. “That one put on four centimeters since 2002,” he added, grinning.